This is the second installment of the “Cousins at War” history I hope to develop into a published article. It records the life of Basil Umney’s cousin, Cecil who also served and died during the Battle of the Somme.

I will be visiting Cecil’s final resting place on the 100th anniversary of his death later this month.

Cecil Francis Umney, Dulwich College Roll of Honour

(Image courtesy of Dulwich College Archives)

Cecil Francis Umney was born on the 7th August, 1896 at 15, Crystal Palace Park Road in the London suburb of Sydenham. His mother and father, William Francis Umney, a medical doctor, and Beatrice Ethel Umney, were already the proud parents of Cecil’s older sister, Muriel Beatrice two years his elder, and the family were soon to be joined by Alan Charles who was born in March 1901.

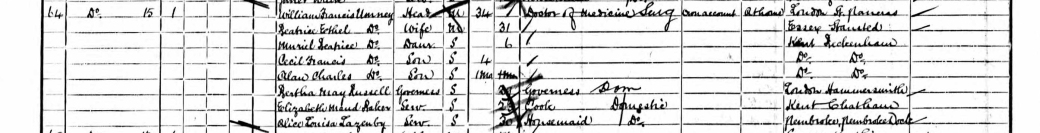

According to the 1901 Census, the family continued to live in Crystal Palace Park Road and employed Bertha May Russell as a governess, Elizabeth Maud Roker as a domestic cook and Alice Louise Lazenby as a household servant.

A close-up of the 1901 Census entry for William Francis Umney’s family and servants whilst living at 15, Crystal Palace park Road in Sydenham.

(Image courtesy of Ancestry Library Edition)

Cecil’s father, William, received his Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons and Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians in 1890, achieved his Bachelor of Medicine in 1891 and qualified as a Medical Doctor in 1892, all after being educated at Merchant Taylor’s School in Northwood. On the 20th June, 1893, William married Beatrice Ethel Carter at St. George’s Church in Bermondsey, and the newly qualified doctor went on to forge a successful career as a consultant physician at the children’s hospital in Sydenham and later as the resident house physician and senior obstetrician at St. Thomas’ Hospital.

Cecil, however, was destined to follow his uncle, John Charles Umney, into the family business, Layman, Umney and Wright. He was educated at The Hall, a preparatory school in Sydenham before attending Dulwich College, and shortly before he left in 1913, he matriculated at London University where he began to study chemistry. Cecil had also secured an apprenticeship with Dr H. Martindale of New Cavendish Street in Marylebone, but on the 9th June, 1915, he also obtained a commission as a Second Lieutenant in the Dorsetshire Regiment. Like his cousin Basil, Cecil’s public school education and Officer Training Corps experiences compelled him to enlist and serve his country, even at the expense of his continuing education.

Initially, Cecil joined the 7th Battalion of the Dorsetshire Regiment, a Reserve unit based at Wareham and later Wool in the Regiment’s home county. Here, he would have undergone training similar to his cousin Basil in the Royal Fusiliers, and begun the unenviable task of learning to lead men in battle and become the father figure they would follow. Daily route marches and physical training would be accompanied by more technical aspects of soldiering such as trench construction and trench warfare.

Cecil would also have had access to official pamphlets and instructions such as “Notes from the Front, Part 3, 1915” which includes a section on the enemy’s ruses:

“The enemy makes use of stratagems some of which we should consider dishonourable. The following are instances:-

- A party of Germans dressed in French uniforms approached a British outpost and speaking French, tried to engage them in conversation. At a given signal they attempted to seize the rifles of our men, and to overpower them. The attempt was frustrated, but not without loss.

- The enemy advanced in the direction of a battalion under cover of a white flag. Instead of surrendering on being approached, they threw down the white flag and forced two companies of this battalion to surrender.”

Whether there was any truth behind these notes isn’t entirely clear, but they would certainly have motivated new officers like Cecil and increased their distrust of the enemy.

On the 17th August, 1916, Cecil arrived on French soil having been attached to the 5th Battalion of the Dorsetshire Regiment as a replacement subaltern. This unit was part of the 34th Brigade of the 11th Northern Division which had only begun to arrive in France from Egypt in July. The Battalion War Diary records that he joined the unit six days later on the 23rd August along with Lieutenant C.J. Richards and Second Lieutenants A.G.W. Grantham, F.A. Damer, S.A. Gomez, A.P. Quaife, C.R.S. Hill, C.H. Hoar and R. Charlton. Having such a large number of replacement officers all arriving at the same time must have been a sobering experience for Cecil and not filled him with much confidence regarding his own personal survival.

At that time, the Battalion was stationed in the commune of Sombrin, west of the city of Arras and behind the northern sector of the Somme battlefront. The next few days saw the unit undergo intense training to allow all of the newly arrived officers and men prepare for their part in the next phase of the Somme offensive.

As August moved into September, the training continued with the Battalion’s strength being recorded as 43 officers and 858 other ranks. However, at 3.30 a.m. on the morning of the 3rd September, the Battalion entrained at Frevent station for a five hour journey to Acheux, which was followed by a route march to Puchevillers. This would have been well within earshot of the front line trenches, so Cecil and his men would have been under no illusions that they were soon to be in action. However, for now, the training continued and after a marching to billets in the village of Bouzincourt on the 8th September, the following week saw additional training, the arrival of more replacements in the form of both officers and other ranks, and the Battalion supplying working parties to help carry out trench and road repairs and move supplies and ammunition up towards the front lines.

The 15th September saw the Battalion standing by to reinforce troops in the trenches, but they were not required until the following day, the 16th September, when the unit relieved the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles opposite Mouquet Farm south-east of Thiepval, starting at 8 p.m. that evening. Over eight hours later, the handing over of the front line trenches was complete, but not without losses. Six men were killed and sixteen others were wounded along with one officer, Lieutenant D.R. Drysdale. The Battalion War Diary recorded the conditions the men faced:

“18th August – Position found to be not as was thought. Mouquet Farm only half taken, not altogether, as was thought by Canadians. Our line found to run through the farm, so that one set of ruins was inside our line, 2 others north of and outside of our lines. These 2 buildings discovered to be stronghold for German snipers. Battalion plan to raid these strongholds and proposed relief of Battalion postponed owing to bad state of trenches from rain. Conditions very trying. Second Lieutenant Russell wounded, Second Lieutenant Hill, Second Lieutenant Prescott and Second Lieutenant Gomez casualties from shell-shock. Other Ranks 2 killed, 7 wounded, 1 missing.”

Seeing three of his fellow officers wounded who had joined the Battalion on the same day as he did must have affected Cecil during his first experience of real trench warfare. Like his cousin Basil a few months earlier, would he have been having second thoughts? Whether he knew of Basil’s death on the 23rd July is unknown, but it is unlikely his parents would have wanted to share such sad and upsetting news.

British troops in the ruins of Mouquet Farm, October 1916.

(Image © and courtesy of the Imperial War Museum Q_1423)

On the 20th September, just three days after taking over the trenches, Cecil and his men were relieved themselves by the 11th Battalion of the Manchester Regiment and soon found themselves in billets in Englebelmer, just west of Thiepval, for “cleaning up and training.”[1]

The day before his death, Cecil and the men of the 5th Battalion, the Dorsetshire Regiment, occupied dugouts in Ovillers in preparation for their part in the next phase of the Somme offensive, the Battle of Thiepval. Both the Battalion War Diary and “The History of the Dorsetshire Regiment, 1914-1919” record in detail the events of that fateful day, the Battalion War Diary first:

“26th – 11th Division had orders to attack. Right of 34th Brigade on R28.c.21. Left on R33.a.54. 9th Lancashire Fusiliers and 8th Northumberland Fusiliers were in front line. Latter on the right, former on the left. 5th Dorset Regiment were in support. 11th Manchester Regiment in reserve.

10.45 a.m: 5th Dorset Regiment moved from Ovillers 10.45 a.m. and took up position in Support Trenches from right to left “B”, “D”, “A”, “C” Companies.

12.35 p.m: Attack started 12.35 p.m. 5th Dorset Regiment followed the front line at about 500 yards distance. Battalion started off well. From information received later the battalion suffered heavily from enemy barrage before reaching the 1st objective, also suffered heavily from bombs, machine guns and snipers from Germans who were still in Mouquet Farm. Could not get any messages back. All Company Commanders and Company Sergeant Majors were knocked out early in the advance. Casualties amongst N.C.O.s were heavy.

8 p.m: Telephone message from G.O.C. 34th Brigade to C.O. to move up Battalion H.Q., collect the Battalion, consolidate 2nd objective with two companies and move two companies up to 3rd objective. Attempted to move up at once but unable to reach the Quarry owing to machine guns and snipers from Mouquet Farm.

10.30 p.m: Started to move up. Encountered enemy barrage on the way to Quarry. H.Q. Company passed up water for men in front. Waited short time in Quarry for barrage to abate. Moved on to High Trench. Found Manchesters working on communication trench, East Yorkshires working on High Trench and Royal Engineers on communication trench forward. Pushed on to R27.d.59. Had picked up Second Lieutenant Nash and Second Lieutenant Vale and about 50 men.”

“The History of the Dorsetshire Regiment, 1914-1919” records the 5th Battalion’s actions during this time as follows, corroborating much of what was recorded in the Battalion War Diary:

“The 34th Brigade’s attack was to be led by its Fusilier battalions, the Northumberlands on the right, the Lancashires on the left. The Dorsets[2]were in support and formed up in Tom’s Cut, five hundred yards behind the frontline. They were to move off when the leading battalions started, and when these advanced against the second objective the 5th Dorsets were to occupy and consolidate the first, in turn sending two platoons per company on to the second objective on the same errand when the Fusiliers pushed forward beyond it. Being in support the Dorsets could remain till 10.45 a.m. in the dug-outs in Ovillers, where they had spent the night. They were in position in ample time and at “Zero,” 12.35 p.m., duly advanced in “artillery formation,” “B” Company on the right, then “D,” “A” and “C. The British barrage was excellent and at first, despite the heavy barrage which the Germans promptly put down, the attack progressed well enough, though as the objectives ran nearly diagonally to the “jumping off” line the left had to mark time to let the right get level. By 12.40 p.m. three waves were reported to have passed Mouquet Farm; by 1.18 p.m. the first objective was reported taken and the leading battalions were making for Zollern Redoubt and Trench. The 5th meanwhile had passed through the first German barrage, which had come down behind our first line with very few casualties, and pushing on, were half-way across No Man’s Land when a second barrage caught them, this time with disastrous effect. Captain Vincent and Lieut. Gandon were killed, Captain Gregory was wounded, and dozens of men went down. Indeed, even before the 5th reached the first objective, High Trench, all four company commanders had been hit quite early on, and companies and platoons had become completely mixed up. Thus, though small parties pushed stoutly on, the attack had lost all cohesion. It was not strange, therefore, that very little information ever came back to Battalion Headquarters, though 2/Lieut. Franklin, who had assumed command of “D” Company when Lieut. King was hit and had led his company forward with great courage and initiative till himself severely wounded, managed to report there on his way to the dressing-station and brought valuable information. It seems that Germans were still resisting in parts of the first objective even after the leading battalions had gone on ahead, so the 5th, instead of starting at once to consolidate, had to fight hard to complete the capture of High Trench and the whole carefully arranged programme went completely to pieces. Some of the 5th, however, pushed on ahead and 2/Lieut. Vale, who took charge of “A” Company when Captain Gregory was hit and handled it most skilfully, established a party quite up close to Zollern Redoubt.”

During this first day of the battle, Second Lieutenant C.F. Umney was wounded and later presumed killed whilst leading his men from the front, just as the O.T.C. at Dulwich College and his later officer training had taught him to. However, due to the confusion and continued fighting, he was reported as missing with his commanding officer recording later that “he went over with his company on 26 Sept., and was slightly wounded; had his wound dressed, and pushed on. He was last seen waving his men on with a bayonet from a shell-hole. The bayonet was seen to fly from his hand, as though he had been hit again. That is all I can find out from his company, but it is enough to show what a gallant end he made.”

The following two days were just as trying for the 5th Battalion, the Dorsetshire Regiment as the 26th September. The Battalion War Diary continues:

“27th – 2 a.m: Enemy sending up a lot of flares 100 yards to our front. Consolidated by digging T. trench. Decided to send out bombing party but no bombs available. Sent out party to reconnoitre. They were driven back by machine gun fire.

6.30 a.m: Manchesters moved up to Schwaben Trench. Dorsets moved up to Zollern Redoubt. Consolidated and established Battalion H.Q. at point north-east R27.b.17. Second Lieutenant Nash with 20 men moved up towards Stuff Redoubt but had to withdraw from heavy machine gun and sniper fire.

10 a.m: Enemy shelling became heavy and continued so throughout the day. Enemy were also very active with snipers and machine guns. Made it very difficult to get up ammunition, bombs and rations.

1.30 p.m: Received orders to attack Hessian Trench with the Manchesters attacking Stuff Redoubt on our left. This order was afterwards cancelled. Continued to consolidate under enemy’s shell fire during the night.”

“28th – Improved communication trench back to Schwaben Redoubt. Enemy shelling still heavy.

4.50 p.m: Received orders to start relief as soon as possible. Enemy shelling became quieter.

5.10 p.m: Started relief.

8 p.m: Reached Ovillers and occupied dugouts there. Casualties during these operations were: Killed – Captain Vincent, Second Lieutenant Elliot, Second Lieutenants Hooper, Gandon and Hughes. Wounded – Captain Gregory, Lieutenant King, Lieutenant Stockwell, Second Lieutenant Franklin, Second Lieutenant Quaife. Missing – Second Lieutenants Slater, Wheeler and Umney. Casualties other ranks estimated at 410.”

“The History of the Dorsetshire Regiment, 1914-1919” sums up what had been a terrible debut for the 5th Battalion:

“The 5th had been sorely tried in their first battle in France and had suffered heavily. Of roughly six hundred in action nearly two-thirds were casualties, eight officers[3] and one hundred and fourteen men being killed or missing, five officers and two hundred and twenty-five men wounded.”[4]

But Cecil’s story did not finish on that day, the 26th September, 1916. His ultimate fate was to remain a mystery for many months to come prolonging the heartache of his parents and siblings who had already lost a dear cousin in Basil Umney just two months previously.

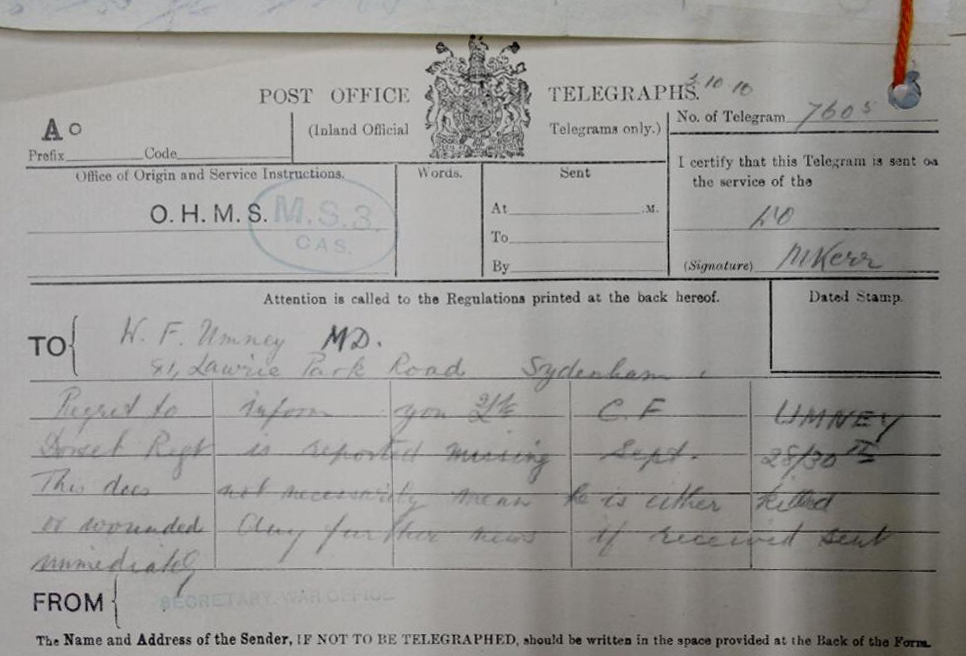

On the 3rd October, a Post Office telegraph was written to Cecil’s father, William. Whilst reporting that Cecil was missing, it remained optimistic stating that this did not necessarily mean he had been killed or wounded and that “any further news if received” would be “sent immediately.”

The original War Office telegram sent to William and Beatrice Umney on the 3rd October, 1916.

(Image © and courtesy of The National Archives)

No further communication regarding Cecil’s fate was received by the family and as time passed the initial optimism created by the telegraph must have eroded away leaving William, his wife, Beatrice and their children, Muriel and Alan fearing the worst.

Sadly, that fear was realised in five months later in March 1917. On the 2nd day of the month, a Field Service report was completed by the Commanding Officer of the 5th (Service) Battalion, Dorsetshire Regiment stating that the body of Second Lieutenant C.F. Umney had been found and buried by a fellow officer, Second Lieutenant T.J.S. Hawtayne of the 36th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. Cecil was identified by the motor licence found among his personal effects, probably in the pockets of his uniform jacket.

Just over a week later, Cecil’s father, William received confirmation of his eldest son’s death in the form of a letter dated the 14th March, 1917 from the War Office:

“The Military Secretary presents his compliments to Mr W.F. Umney and deeply regrets to inform him that a report has just been received which states that Second Lieutenant C.F. Umney, Dorset Regiment who was previously reported “Missing” is now reported to have been “Killed in Action on September 26th, 1916, and his body found.”

The Military Secretary is desired by the Army Council to express their deep sympathy.”

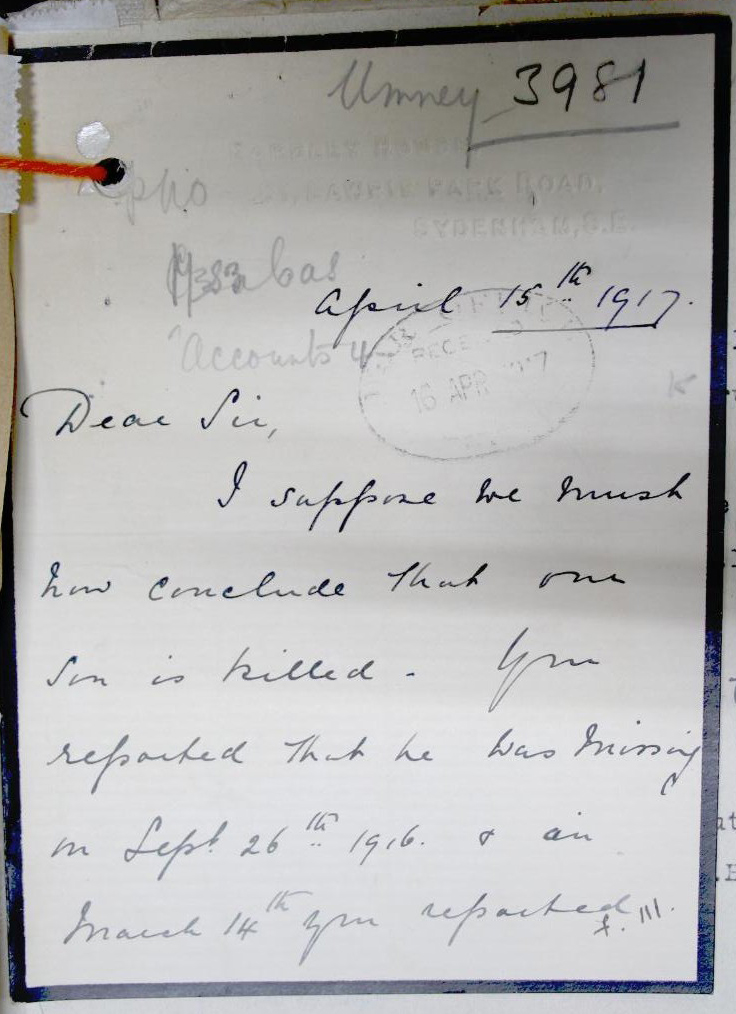

The effect of this news on the family, whilst possibly expected after over five months of silence, was obviously devastating. It wasn’t until the 15th April, 1917, that William wrote a letter back to the War Office:

“Dear Sir,

I suppose we must now conclude that our son is killed. You reported that he was missing on Sept. 26th 1916 and on March 14th you reported that his body had been found and buried. Will you kindly let me know what money is owing to him, so that I may proceed to settle his affairs.

Yours faithfully,

W.F. Umney

My son’s name is

2nd Lieut. Cecil F. Umney, 5th Dorset Regt.”

The first page of William Umney’s letter to the War Office dated 15th April, 1917.

(Image © and courtesy of The National Archives)

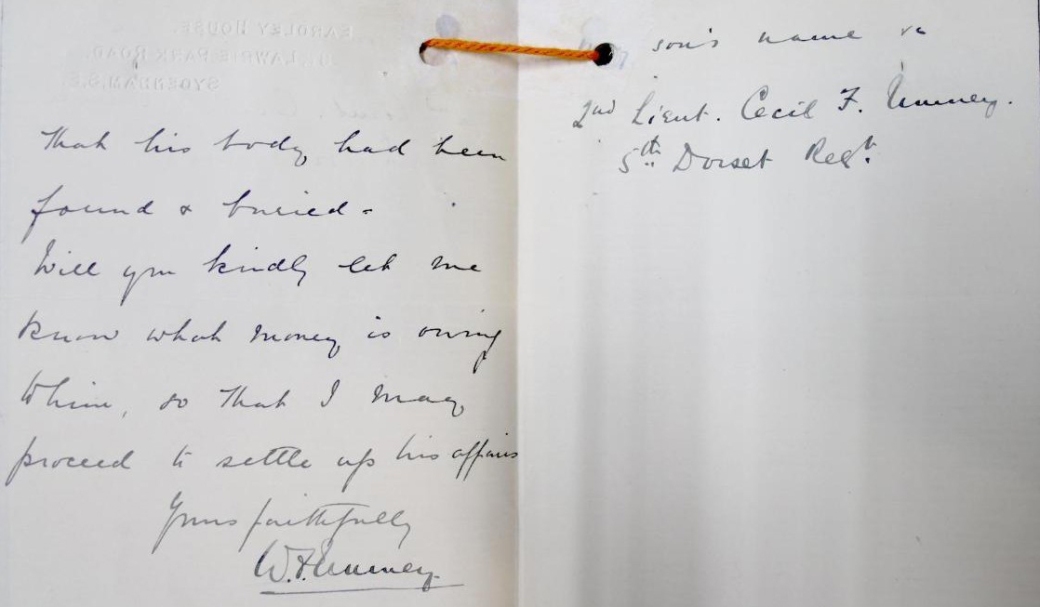

The continuation of William Umney’s letter to the War Office dated 15th April, 1917.

(Image © and courtesy of The National Archives)

The Certificate of Death for Cecil was issued on the 6th June, but as he had written no will, his personal effects and financial accounts could not be dealt with straight away. However eventually, after much correspondence, William received his son’s motor licence back and Army wages worth £68 and 5 shillings. In addition, after the war’s end, Cecil was awarded the British War and Victory medals along with a Dead Man’s Penny and scroll from King George V and a grateful British government, but none of this could assuage the loss to the family of Cecil.

It isn’t known if William, Beatrice and their children ever visited Cecil’s final resting place, but his grave can be found in Regina Trench Cemetery not far from the Somme commune of Grandcourt. The inscription on his headstone includes a tribute to his cousin, Basil who, killed two months previously and with no known grave, is remembered here as well as on the Theipval Memorial to the Missing. It reads: “Also in memory of 2nd Lt. B.C.L.Umney 4/R.Fus. Killed in Delville Wood July 23 1916.”

Regina Trench Cemetery near the Somme commune of Grandcourt.

(Image courtesy of James Robertson)

The war grave of Second Lieutenant C.F. Umney, Regina Trench Cemetery. The additional inscription commemorating Cecil’s cousin, Second Lieutenant B.C.L. Umney can be seen at the base of the Portland stone marker (below)

(Image courtesy of James Robertson)

Although they were not killed on the same day or on the same part of the Somme, they rest together on the battlefield they fought and died on leading their men from the front.

Lest we forget.

References:

[1] 5th Battalion Dorsetshire Regiment War Diary, The National Archives

[2] “The Second in Command and a proportion of officers and N.C.O’.s were left behind at Bouzincourt, to form “battle nucleus” on which the Battalion might in case need be built up again.”

[3] “Captain Vincent, Lieuts. Elliott, Gandon, Hooper, Hughes, Slater, Umney and Wheeler.”

[4] “History of the Dorsetshire Regiment, 1914-1919” by various, pgs. 49-50 & 53.

Bibliography:

Books:

- “Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War” by John Lewis-Stempel, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2010.

- “An Officer’s Manual of the Western Front 1914-1918” compiled and introduced by Dr Stephen Bull, Conway, London, 2008.

- “History of the Dorsetshire Regiment, 1914-1919” by various, Naval & Military Press, 2002.

Websites:

- Ancestry Library Edition – 1901 England Census, British Army Medal Record Index Card, 1914-1920, Du Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour.

- The National Archives – http://www.thenationalarchives.gov.uk – Battalion War Diary, 5th Battalion Dorsetshire Regiment, WO95-1820-1; Lieutenant Cecil Francis Umney, the Dorsetshire Regiment, WO339/2852.

- The Commonwealth War Graves Commission – http://www.cwgc.org

- The London Gazette – http://www.thegazette.co.uk

- The Long, Long Trail – http://www.longlongtrail.co.uk

Archives:

- Dulwich College Archive – The Dulwich College Roll of Honour

Remembering the Somme 100 years on – Second Lieutenant Cecil Francis Umney and the 5th Dorsetshire Regiment

The 26th September, 2016 marked the 100th anniversary of the death of Second Lieutenant Cecil Francis Umney of the 5th Battalion, the Dorsetshire Regiment during the Battle of the Somme.

During a visit to the battlefields in late September 2016, I was fortunate to visit the war grave of my ancestor 100 years to the day of his unfortunate passing, and see the area of the battlefield he fought and died in.

The entrance to Regina Trench Cemetery with the Cross of Sacrifice (left) and the Stone of Remembrance (right).

The war grave of Second Lieutenant Cecil Francis Umney, 7th (S) Battalion Dorsetshire Regiment, killed in action on the 26th September, 1916.

Cecil’s cousin, Basil, a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Fusiliers killed at Delville Wood on the 23rd July, 1916, is also commemorated on this war grave.

An unexploded shell uncovered by ploughing in the agricultural fields surrounding Regina Trench Cemetery.

The Australian Memorial outside Mouquet Farm, the objective of the 7th (S) Dorsetshire Regiment on the 26th September, 1916.

Mouquet Farm (left) and view back towards the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing, terrain Cecil and his men would have had to cover to reach their objective.

The Dorsetshire Regiment Memorial near Authuille Wood.

All photographs © and courtesy of James Robertson.